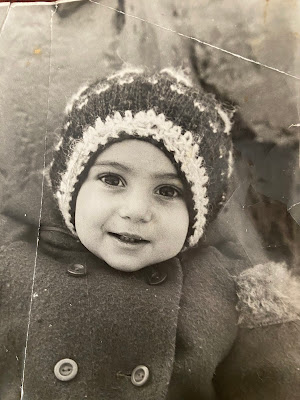

My American Dream. Growing Up Armenian in Crimea.

There are moments in life when a dream is more than just a dream—it becomes a lifeline. As a child growing up Armenian in post-Soviet Crimea, I clung to a vision of America like it was a warm, faraway light at the end of a long, narrow tunnel. It wasn’t just about a country; it was about escape. Escape from poverty, from ridicule, from never quite belonging. I imagined a world where no one mocked my features or my name, where I could be myself without apology. This is the story of that dream—how it began, how it shaped me, and how I’m still searching for the place I can call home.

As you know, I’m of Armenian descent, but I was born and raised in Crimea—a region that has always been predominantly Russian. From a young age, I faced bullying because of my Armenian looks and background. On top of that, Ukraine after the fall of the Soviet Union was a country in crisis. Most people barely made ends meet. We often didn’t have enough food, I wore hand-me-downs, and evenings in our town were dark and cold—there was no electricity or hot water.

In the 1990s, my mother’s younger brother was murdered while working as a bartender at an Armenian restaurant in Kyiv. The restaurant owner — also Armenian — had allegedly owed money to someone, and a hitman was hired to settle the score. But the hitman, who didn’t like non-Slavic people, opened fire on all the Armenians he encountered that day. My uncle was among them. He was only 33 years old, with a wife and two small children waiting for him at home. That experience planted in me, even as a child, the deep-rooted feeling that I wasn’t truly safe in the country I was born in.

When I was eleven, my father’s older sister, who lived in California with her children, kept encouraging him to move our family to America. But he refused. That was when my obsession with America began. I was captivated by 90s American movies and the lifestyle they portrayed. I dreamed of walking the halls of an American high school, eventually going to college there, and most of all, starting over in a place where no one would mock my appearance or heritage.

I imagined America as a true melting pot where I could belong.

There was also a more practical reason: survival. I dreamed of a better life. I longed for stability and opportunity. My obsession ran so deep that when I was hospitalized with pneumonia at the age of eleven, I dreamt I was skiing with Bill Clinton. (I should mention I had a congenital heart condition that affected my lungs, so I was frequently in and out of the hospital. And let’s just say that Ukrainian hospitals in the 90s are a story for another time.)

Because of my health, I was homeschooled for a few years, and my school couldn’t provide English teachers for home instruction. I started learning English later than most Ukrainian kids—but I was determined. I spent hours at the library looking for textbooks, studying vocabulary, practicing every single day. Eventually, I became more fluent than most of my peers.

At fifteen, I discovered a language program in town taught by Americans. I secretly applied, passed the entry tests, and was accepted. My parents couldn’t afford the tuition, but I begged and pleaded until they agreed to make it work. Those English lessons were the highlight of my teenage years. Five days a week, two hours a day—I was in my element. My American teachers were incredibly kind, perhaps because they were also Christians. They were more accepting and warm than most people in my town. In fact, I’m still in touch with some of them 24 years later.

Later, I studied languages at university and earned a master’s degree. Throughout my teens and early twenties, I spent time with American Mormon missionaries and Christians from church communities. Those friendships became a lifeline for me.

But everything changed in 2014 when Crimea was annexed. All foreigners were expelled, and my social circle disappeared overnight. That was when I started to isolate myself. I wasn’t interested in meeting Russians or Ukrainians anymore. A few of my good friends—Russian and Korean—moved abroad, leaving me further disconnected. And now, during the war, it’s impossible for foreigners to enter Crimea. I feel more cut off than ever.

For as long as I can remember, I’ve felt like I didn’t belong here. Like I was a guest in someone else’s country. Even my own brother, who I always thought didn’t mind living here, was also bullied as a child. But instead of embracing his Armenian identity, he chose to assimilate. He doesn’t speak Armenian, doesn’t have Armenian friends, has never been to Armenia even though he could afford to visit. He doesn’t know the names of our dad’s many siblings or much about our heritage. He married a Russian woman and built a life that deliberately distances him from who we are. His response to bullying was to blend in. Mine was to hold on tighter to where I come from.

That might explain why I avoid Russian men. I don’t date them, don’t entertain conversations—I can’t help it. I’ve been carrying this resentment for years.

A lot of Armenians in Russia don’t speak Armenian, unlike in other parts of the diaspora. In my opinion, it’s because of xenophobia and pressure to conform. For many, it’s safer to erase parts of themselves.

I visited Armenia a few years ago, hoping to feel something familiar—some spark of connection. But I felt like a foreigner there too. Too Armenian for Russians, too Russian for Armenians.

So where do I fit in? I still don’t know where I truly belong. Not in Crimea, where I’ve always felt like a guest. Not in Armenia, where I’m a stranger with a familiar name. And not even in America, the land of my childhood dreams, which now feels more like a symbol than a destination. I’m still trying to figure it out. I’m sharing this not to place blame — I know many Armenians have found a sense of belonging here, and I respect that. But this has been my experience: one of feeling caught in between cultures, searching for a place to simply be myself without explanation.

If you’ve ever felt like you don’t fully belong anywhere — not here, not there - I hope this post reminds you that you’re not alone. Maybe, in telling my story, I can help someone else feel seen in theirs.

“I’m too foreign for here, too foreign for home — never enough for both.”

— Ijeoma Umebinyuo

Comments

Post a Comment